|

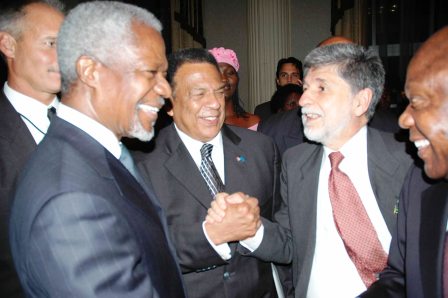

Farewell to the

Secretary-General

E. Ablorh-Odjidja

January 03, 2007

For generations to come, and

especially for Africans, the name Secretary-General will

perhaps attach mostly to one person, Mr. Kofi Annan.

He served as the

Secretary-General of the United Nations and retired

after his ten-years term on December 31, 2006.

Whether historians will recognize

Mr. Annan as one of the greatest Secretary Generals of

all times or not remains to be seen. But those around

today should note immediately that none of his

predecessors experienced half the difficulty that faced

Mr. Annan during his term in office.

Mr. Annan’s term was the most

turbulent – from wars to natural disasters. But he saw

it all through with the coolness that some said was at

the core of his character.

First, there was the Iraq crisis

of 2003. Before this, Mr. Annan was deemed by most as a

very popular world citizen. And even with what seemed

like a hostile US President Bush administration in

office, he was awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 2001.

But soon things began to change

in Mr. Annan’s orderly world.

The key difficulty during this time came under

the guise of the “Oil for Food” scandal and he almost

fell victim to it.

The “Oil for Food” policy” was in

place in 1996, and was supervised by the UN to allow

defeated Iraq to sell some of its oil for food.

By mid-May 2004, the food

program’s supervision had become a full scandal.

Mr. Annan’s opponents in the US

administration at the time, who had grudges against him

for opposing the 2003 war with Iraq at the start, were

not deterred by the glowing tributes he had garnered so

far.

Instead, they chose to use the food scandal as a

retrospective excuse to call for his immediate ouster.

The Wall Street Journal editorial

of November 17, 2004, read as follows:

“(A) United Nations that allowed

Saddam Hussein to embezzle at least $21.3 billion in oil

money during 12 years, with the great bulk of that

sum--a staggering $17.3 billion--pilfered between

1997-2003, on Mr. Annan's watch…”

The Wall Street editorial

must have known

when the die

for his supposed ouster was cast.

A Dr. Nile Gardiner, writing for

the Heritage Foundation’s website, said that Mr. Annan’s

“failure of leadership relating to the U.N.’s

administration of the Oil-for-Food program .. cast

serious doubt over his suitability to remain in office

while the scandal is investigated.”

Of course, the case against Mr.

Annan was staged by those who wanted to punish him for

his reluctance to go along with the effort to oust

Saddam Hussein from power.

So, instead of a serious look at a flawed concept

that the UN Security Council had hatched, namely the

“Oil for Food” program, Mr. Annan became the scapegoat

and the target.

The program had its beginning in

1991, some five years before Mr. Annan was appointed the

Secretary-General. It came when the UN got apprehensive

about the worsening humanitarian situation in Iraq after

Gulf War I.

Under the “Oil for Food” program,

Iraq was permitted to sell some oil to meet pressing

humanitarian needs. A major portion of the revenue, 59%

to be exact, was to go to the government of Iraq for

essential supplies.

“It was the basic assumption that

Iraq – not the United Nations – would choose its (Iraq)

oil buyers,” said the Volcker committee, which was

appointed to look into the scandal, in a report in

October 2005.

Assumption or not, it was Saddam

Hussein who manipulated the program to his advantage.

The result, as the Volcker committee said, was that he

“selected oil recipients to influence foreign policy and

international opinion.”

The report, unfortunately, did

not ask why the UN Security Council allowed itself to

commit such a blunder. Or why it designed a chicken coop

and chose a fox-like Saddam to guard it!

Instead of blaming the UN

Security Council, it became sufficient for Mr. Annan’s

detractors to assume that Mr. Annan was the designer in

chief of the program for his benefit, and perhaps those

of a few cronies.

In reality, the intent to

prosecute Chief Annan had a different origin, one that

in cases like this was not openly mentioned.

As a chief spokesperson for the

UN, Mr. Annan had come out against the pending 2003 Iraq

war, with a strong anti-war sentiment that was too

uncomfortable for the Bush administration because it was

close to the presidential re-election of 2004.

Mr. Annan’s anti-war expression

went against the political sentiment of an

administration that was anxious to punish Saddam for the

9/11 crime, for fame and for possessing "weapons of mass

destruction.

And soon, the bad press started

rolling and the intensification of the cries for his

resignation mounted in earnest.

Mr. Annan became fodder for the US ideological

rivalry. The “Oil for Food” crisis was the

retrospective excuse.

Why a UN Secretary-General should

not want war would be an oxymoron question to ask. But

some did ask. Surprisingly, somebody forgot to point out

to them what the UN stood for.

The UN was established to resolve

conflicts between nations.

Whether for war or peace, the Secretary-General,

in this case, Mr. Annan, should be allowed the

flexibility to wage either.

How a Secretary-General came out

of any situation of such belligerence, either for peace

or war, ought to be the litmus test of his success or

failure in office at the UN.

The mess and the lies exposed, of

the Bush administration after the Iraq war, ought to

show that Mr. Annan was rather prophetic and wise for

going against it and for promoting caution.

No matter how much nations

profess peace, there are bound to be differences at the

UN, some pushing for war and others for peace.

But there is the Security Council within the UN,

with the power to override any proposal for war or

peace; that often have had crippling effects

on world peace.

Exemplar cases are the ongoing

conflicts in Somalia, Darfur, Sudan, and this “Oil for

Food” program under which Mr. Annan has just been

crucified.

Instead of looking to the

Security Council for blame, Mr. Annan’s opponents wanted

to put it on him.

The same permanent powers at the Security

Council who had approved the handling of the “Oil for

Food’ program - France, Britain, and Russia - had

supported entities that aided Saddam to hoodwink the UN.

Yet the same wanted to blame

Secretary-General Annan.

In truth, Mr. Annan affirmed the

usefulness of the “Oil for Food” program as “the only

humanitarian programme ever to have been funded entirely

from resources belonging to the nation it was designed

to help.” He had

said so in a statement to the Security Council on

November 20, 2003.

He also added that the program

had “an almost impossible series of challenges."

He was right in

his description. But perhaps, he should have gone

further to point the blame at the Security council.

Significantly, Mr. Annan was

spared by the Volcker committee. Could the whole

scandal have been an attempt to hurt the glorious legacy

he had achieved during his first term?

Many statesmen, looking at Mr.

Annan’s career and his relationship with the UN, portray

him as a skilled bureaucrat and a believer in the UN

system.

The BBC in a profile about him

must have found Mr. Annan’s core belief when it reported

Mr. Annan’s claim that the “UN should act on behalf of

not just the major powers but all states.”

Mr. Annan was right.

And with the strength of character, he held on to

this belief to the end of his official term.

E. Ablorh-Odjidja, Publisher,

www.ghanadot.com, Washington, DC, January 03, 2007.

Permission to publish: Please

feel free to publish or reproduce, with credits,

unedited. If posted on a website, email a copy of the

web page to publisher@ghanadot.com. Or don't publish at

all.

Back to

commentary page

|